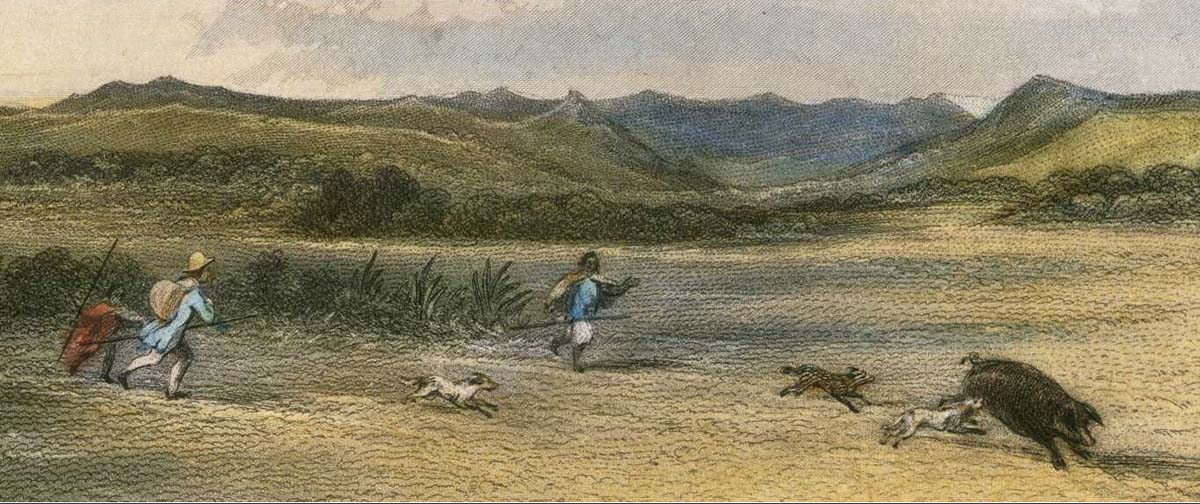

Maori and European hunting pigs in the lower Wairarapa in 1847 (painting by Samuel Brees), see Mair 1979: 13).

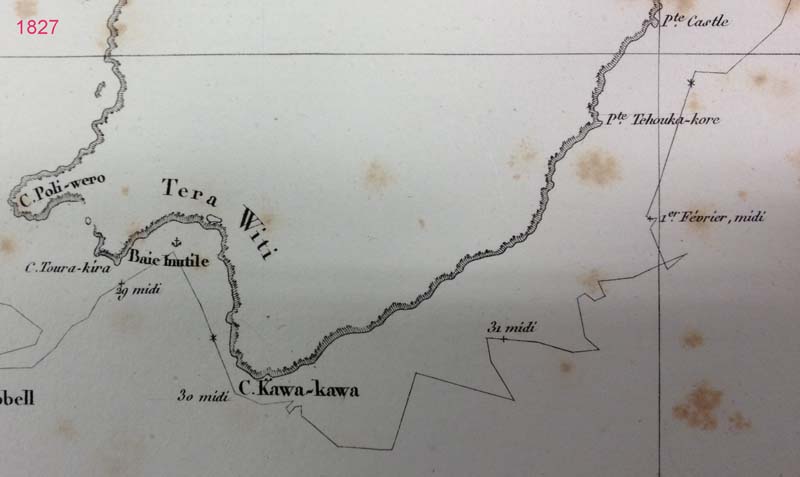

"The first direct contact between Maori of the Wairarapa and Europeans occurred on a hazy summer's afternoon on February 9, 1770. when three canoes were paddled up to the 'Endeavour' off the East Coast north of Cape Palliser. The Maori immediately asked for nails which, Cook observed, they had never seen before but evidently knew how to use. He surmised that they had gained their information from the people of Cape Turnagain whom he had visited the previous year (Cook, 1955: 250). Thus, the protohistoric in the Wairarapa may be reasonably held to begin with Cook's first contact with the Maori further north on October 9, 1769. The next visitor was Captain Furneax who in 1773 was forced inshore to Cape Palliser by squally weather and there traded nails and Tahitian cloth for crayfish brought out to the 'Adventure' in canoes (Cook, 1961 (2): 471). Several weeks later Cook, searching for the 'Adventure', sailed along the shore of Palliser Bay and noticed some smoke inland but no inhabitants (Cook, 1961 (2): 299).Twenty-two years may have passed before Europeans again cruised the Wairarapa coast. The whaler 'England's Glory' was reported to have contacted Maori in this area (Wilson, 1939: 126-129). although Mackay (1966: 80) is rather sceptical of this unverified report. A similarly unverified eighteenth century contact is the Maori tale of the wreck of 'Rongotute' (Best, 1912: 26-27). Smith (1899: 203) has suggested it might have been the 'Coquille' which disappeared without a trace after setting out for New Zealand in 1782.

With development of whaling in New Zealand waters a number of ships passed through Cook Strait in the early decades of the nineteenth century, but apparently only the 'Astrolabe' under D'Urville entered Palliser Bay. D'Urville was unable to land but met a number of the inhabitants nevertheless and observed numerous huge fires burning inland (Wright. 1950: 105). By the 1830s whaling stations were being established at Te Awaiti [Tory Channel, Queen Charlotte Sound], Mana Island, Porirua, and Kapiti Island, and the traffic in the Straits consequently intensified. Rather infrequently, some of these ships entered Palliser Bay and, on at least one occasion - the 'Active' in 1836 (McNab. 1913:1 43-144) - became temporarily embroiled in the local upheavals occurring through the expansion of the Ngati Toa and their allies in the Wellington district as a whole" (Mair, 1978: 11).

For almost all of the 800 to 1,000 years of Maori occupation of the Wairarapa, the inland reaches saw only sporadic and temporary visits. The inland areas of the Wairarapa valley did not possess adequate food resources of the right kind that could sustain permanent habitation.

By contrast, the coastal flats on both sides of Lake Onoke and up the east coast were the places where permanent villages were established. Even here, life was tough, and periodic food shortages took place. This has been shown by the presence of Harris Lines in X-Rays of long bones, which attest to serial bouts of starvation (Sutton, 1979: 197).

The reasons for this contrast between the different opportunities for sustained settlement in the coastal and inland areas are complex, but relate to some fundamental requirements of human diet and nutrition. Human survival depends upon an adequate source of caloric energy which is obtained from consuming protein, fat and carbohydrate. Protein is needed for the essential amino acids that are used for building and maintaining tissue cells in the body, and if there is an excess over needs the remainder that is injested is used as caloric energy. However, energy from protein must not exceed 30% of caloric intake for any length of time, otherwise serious disease will follow, including starvation (known as rabbit starvation from eating too much lean meat).

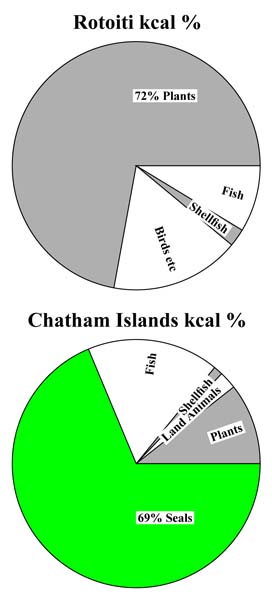

The additional 70% of caloric energy that must be obtained from something other than protein comes from foods rich in either carbohydrate or fat. Carbohydrate normally comes from starchy foods, such as kumara and potato. However, some human communities live perfectly satisfactory lives without any access at all to starchy foods, and get the all important 70% caloric energy solely from the consumption of fat (Leach 2006: 235 ff.). To the left is an illustration of two quite different solutions to the problem of obtaining enough caloric energy from non meat sources in pre-European New Zealand. At Rotoiti protein is estimated as having provided 16% of caloric intake, fat 17%, and carbohydrate 67%. So this is well above the 70% threshhold of safety. In the Chatham islands quite a different solution was found, with caloric energy input from protein contributing 31%, fat a whopping 60%, and carbohydrate 9%. This is slightly under the safety threshold (Leach 2006: 272).

1

The additional 70% of caloric energy that must be obtained from something other than protein comes from foods rich in either carbohydrate or fat. Carbohydrate normally comes from starchy foods, such as kumara and potato. However, some human communities live perfectly satisfactory lives without any access at all to starchy foods, and get the all important 70% caloric energy solely from the consumption of fat (Leach 2006: 235 ff.). To the left is an illustration of two quite different solutions to the problem of obtaining enough caloric energy from non meat sources in pre-European New Zealand. At Rotoiti protein is estimated as having provided 16% of caloric intake, fat 17%, and carbohydrate 67%. So this is well above the 70% threshhold of safety. In the Chatham islands quite a different solution was found, with caloric energy input from protein contributing 31%, fat a whopping 60%, and carbohydrate 9%. This is slightly under the safety threshold (Leach 2006: 272).

1

The upshot of all this is that trying to live in the Wairarapa valley for any length of time would have been virtually impossible for pre-European Maori for the simple reason that kumara could not be grown there because of the danger of frosts. In addition, there were inadequate sources of fat as an alternative to carbohydrate. This conclusion is confirmed by the complete absence of any archaeological evidence of substantial settlements older than about 200 years in the interior valley. By contrast, coastal Wairarapa has hundreds of sites, many dating back to the earliest period of New Zealand prehistory.

I have no doubt that many small camp sites do exist in the main valley, dating throughout the pre-European era, but these could only have been short duration sites, such as those left by groups hunting for birds and collecting forest resources to take to their permanent villages along the coast.

Everything Changed When Potato and Pig arrived in New Zealand

There is no doubt that both pigs and potato became available to coastal Wairarapa Maori considerably earlier than when the first Europeans ventured into the Wairarapa valley. Permanent or semi-permanent occupation by Maori of the inland areas quickly followed this introduction. The evidence for this is as follows:

Captain Cook made several attempts to introduce pigs, chickens, potatoes, and many other plants into several parts of New Zealand during his five visits here (once on the first voyage 1769, three times on the second voyage 1773-4, and once on the third voyage 1777). Of special relevance to the Wairarapa, he gave pigs, chickens, cocks and potatoes to Maori people who visited the ship when he passed Black Head, just north of Porangahau.

2

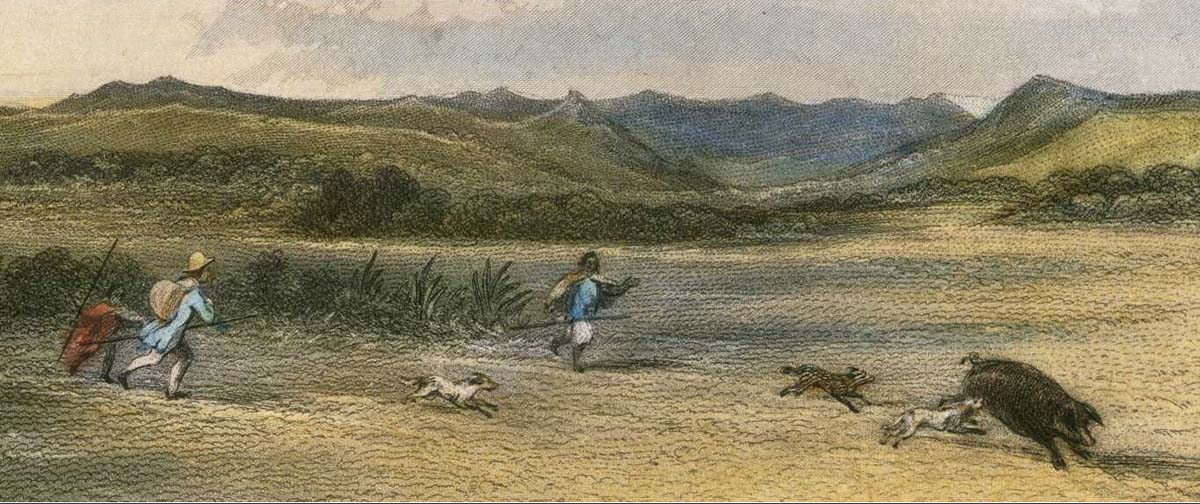

By the time D'Urville was along the east coast in 1827, pigs and potatoes were plentiful in Tolaga Bay, and it is safe to assume that they had spread far beyond, including southwards to Wairarapa.

3

A reasonable estimate for the first permanent Maori villages in the main Wairarapa valley would therefore be from around 1800 on. By the 1820s, the whole southern area of the North Island became enmeshed in the adventures of Te Rauparaha and Taranaki invaders. Such were the problems in the Wairarapa valley that Ngati Kahungunu took part in a mass exodus to Nukutaurua, on the Mahia Peninsula, which is dated to 1834. They returned to Wairarapa 1840-1841 (Bagnall, 1976: 12-14).

So far as is known, the first European to venture into the valley was Ensign Best in December 1840. Best came around the coast from Wellington, and while he was in the vicinity of the abandoned Battery Hill pa, his party engaged in protracted pig hunting (Bagnall, 1976: 26).

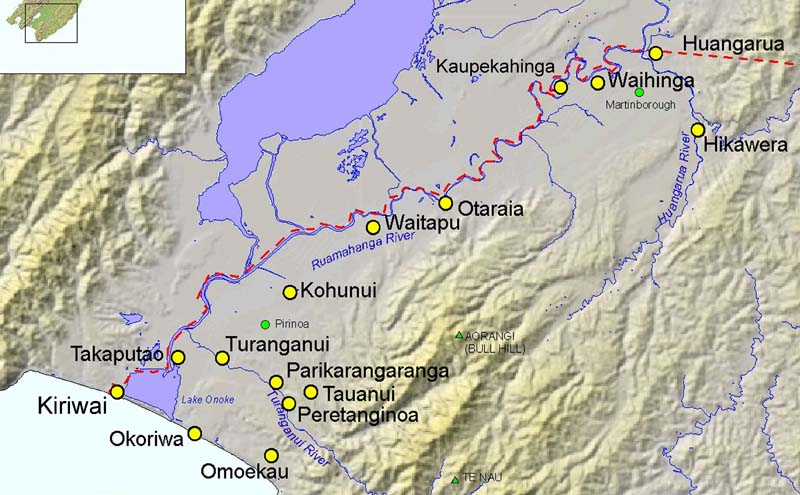

The important point to remember is that by the time Europeans began to take an interest in the Wairarapa valley, it was already settled by Maori in permanent villages, with potato gardens and access to abundant feral pigs. Pigs are easily domesticated, and some of these villages may well have kept them for fattening and breeding. The map below shows the location of some of the better known Maori villages which were occupied before the first Europeans came into the valley.

The introduction of these two new food sources into New Zealand was of profound importance to Maori people. Potato is far more reliable than kumara, and could be grown in areas where kumara could not survive the cold temperatures of winter. Moreover, the potato yield is far higher for the same area under cultivation, and is much easier to store until the following harvest takes place. This new source of carbohydrate permitted a surplus to be produced, and to the early historic Maori was similar in impact to that of the Neolithic revolution in Europe. The ability of any society to produce and store a surplus of food releases large numbers of people from the day-to-day struggle for survival. In Europe, Asia, and the Americas it led the way to the development of city states and civilisation as we know it. For New Zealand Maori in the southern North island and all of the South island, the appearance of potatoes permitted not only a surplus of energy-rich carbohydrate, but the ability to store it for long periods. Added to this, pigs provided a ready source of fat-rich meat throughout inland areas that hitherto was absent. This too permitted year-round occupation of areas away from the coast in the main Wairarapa valley.

Charles Heaphy is arguably one of the first Europeans to have set eyes on the great expanse of the Wairarapa valley. Accompanied by Ernst Dieffenbach, he set out up the Orongorongo valley and from the top of the range viewed the expanse of the two Wairarapa lakes and Palliser Bay in September 1839.

Charles Heaphy is arguably one of the first Europeans to have set eyes on the great expanse of the Wairarapa valley. Accompanied by Ernst Dieffenbach, he set out up the Orongorongo valley and from the top of the range viewed the expanse of the two Wairarapa lakes and Palliser Bay in September 1839.

William Deans was the first brief visitor to the valley in October 1840. He took the coastal route from Wellington, and went along the western side of Lake Onoke as far as Battery Hill, noting that the pa there was abandoned at the time. He worked his way up to the peak now known as High Maunganui, south of Waiorongomai, to take bearings, and then returned southwards back to Wellington.

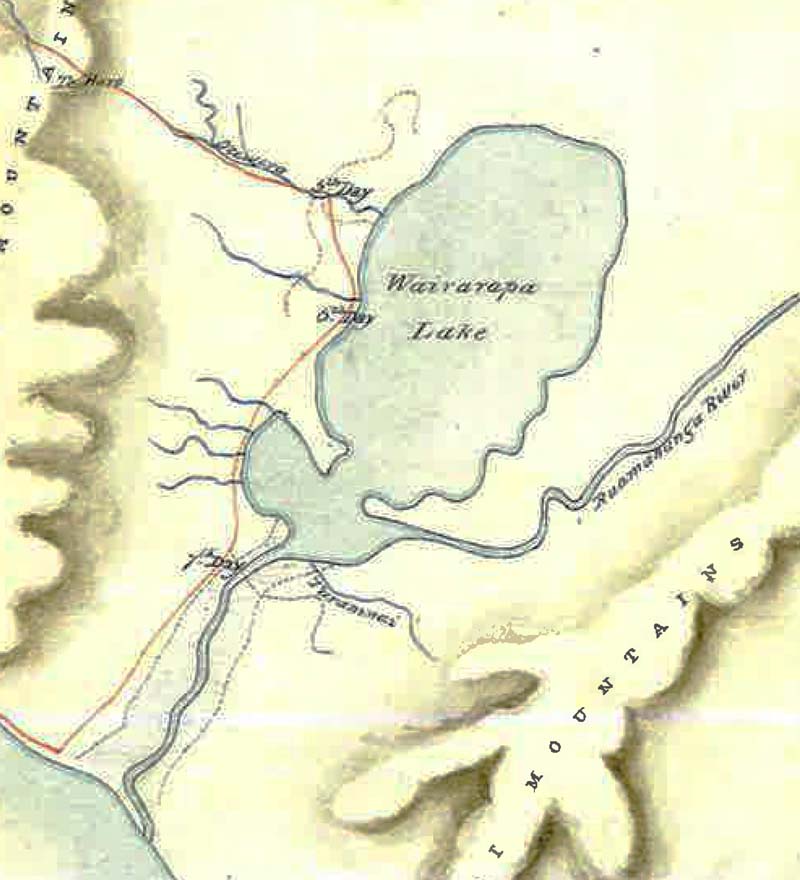

The next person to sight the Wairarapa valley was Robert Stokes, who crossed the Rimutaka Range in November 1841 and continued southwards along the banks of Lake Wairarapa. He returned to Wellington via Cape Turakirae.

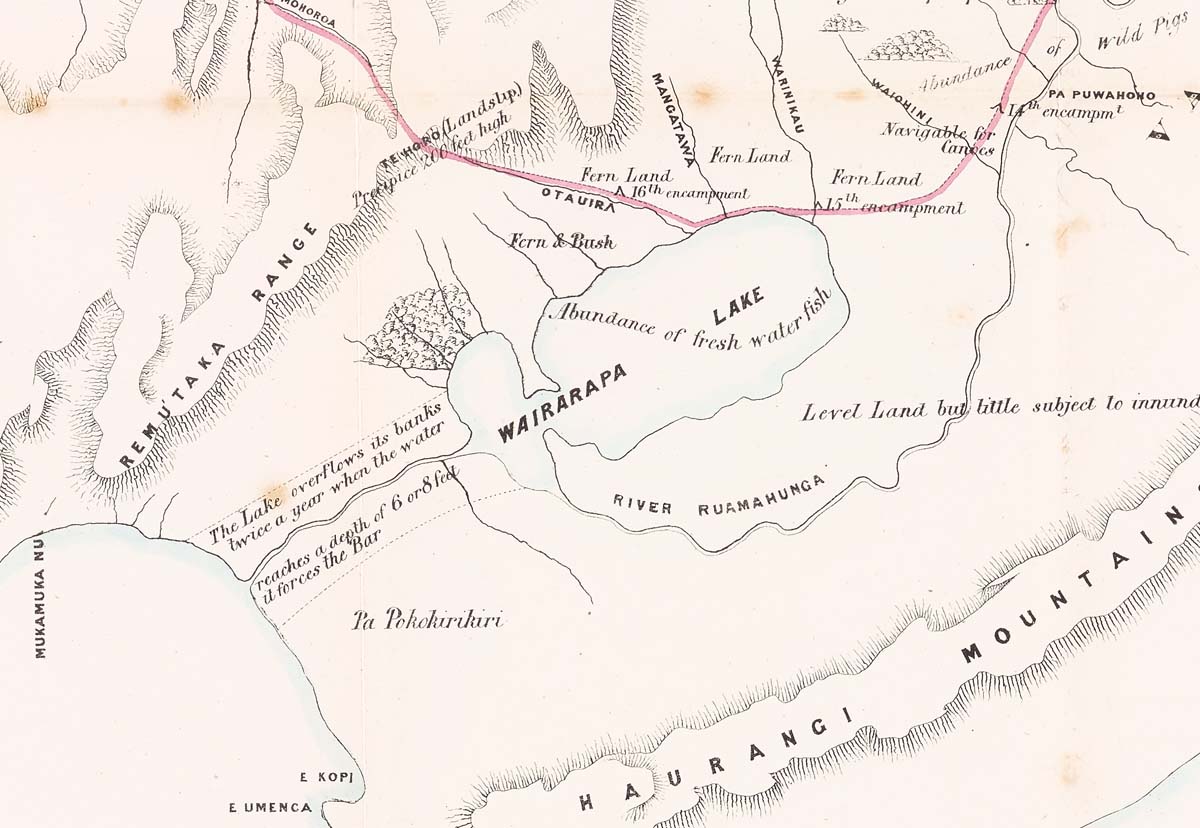

In May 1842 Charles Kettle and Arthur Wills embarked on a sojourn from the Manawatu gorge southwards. They came across Maori potato gardens at Kaikokirikiri pa (near Masterton), and wild pigs at Waiohine (Bagnall 1976: 28-33). They suffered a number of privations on their way south, and did not venture to the east of the Ruamahanga River, so their journey sheds little light on Maori occupation of that area in 1842. A sketch map of the area was published in a book by Whitehead (1848)

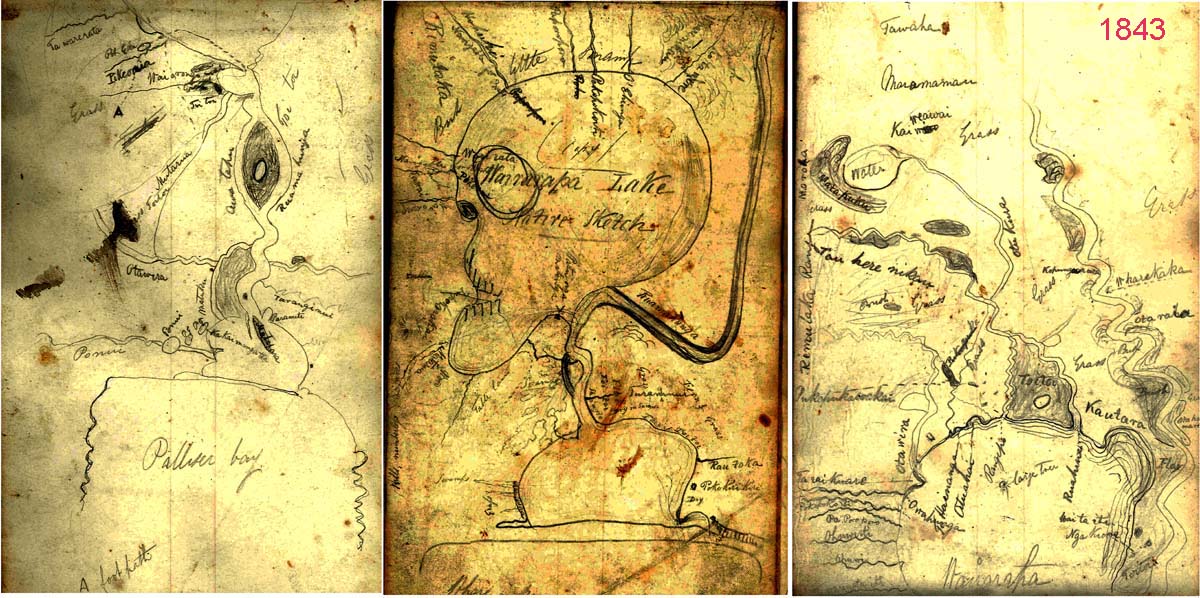

The next important visit in February 1843 was by Samuel Brees with Hugh and John Cameron, Richard Barton, and Edward Chetham. They crosssed over the Rimutaka range, and went south as far as Tauanui pa on the Turanganui River, and from there back to Wellington via the coast (Bagnall, 1976: 33). Brees left some wonderful paintings for posterity, depicting the forest and grassland landscape of the lower Wairarapa; however, few useful details of contact with Maori are available. A sketch map of their sojourn does not show Lake Onoke.

On his second trip in July 1843, he was assisted by F.J. Tiffen who made an astonishing map of Lake Onoke and Lake Wairarapa (see below). The first of the three maps, on the left, gives Maori place names from Lake Onoke to Waiorongomai, preumably from Maori informants. It is interesting that Matarua is named. This is a small isolated forest of karaka trees, still existing today. Colenso later records Wairarapa Maori preparing and eating karaka, sometimes with deadly results. The second map is labelled "Wairarapa Lake, Native Sketch" and the lake is whimsically depicted as a human skull. Again, it is covered in Maori place names. Note Pa Kokirikiri is shown beside Lake Onoke, and south of the Turanganui River. The map on the right shows the area to the north of Lake Wairarapa, and includes Kautara [Kahutara], Otaraia and Wharekaka.

The next significant journey into the Wairarapa valley was by Henry Harrison and Joseph Thomas in October 1844. They visited Upokirikiri and Wharekaka, and then crossed eight miles of a grassy plain to a small settlement called Huangarua at the foot of a hill beside the river of the same name (Bagnall, 1976: 38-39). The exact location of this village is not clear.

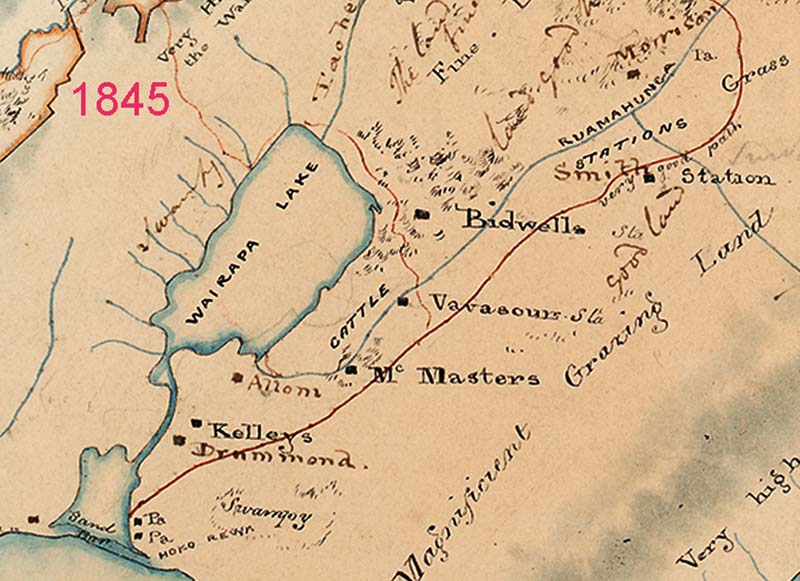

Below is part of a map of the stations that existed in the lower Wairarapa valley by 1845. The red line shows the regular trail that Europeans used, labelled "very good path". Note that it crosses over the Ruamahanga on Morrison's estate, south of the Waiohine. Kiriwai pa (not named) appears on the west of the sand bar, and two other pa are shown in the vicinity of Lake Ferry. One is named Hoko Rewa [Okorewa]. Named stations are: Smith (just south of what must be Huangarua River, not named), Bidwill, Vavasours, McMasters, Allom, Kelleys, Drummond,

Colenso visits the Wairapapa Valley

Two years later, Colenso observed that the fortifications at Otaraia were crumbling, and that at Huangarua the huts were decaying. On his last trip, in 1850, he observed "The heart seemed to be going out of the Wairarapa villages, however, for at Huangarua a third of the people had died during the prevous ten months. Sickness and poverty marred Te Kaikokirikiri" (Bagnall and Petersen, 2012: 290).

Kemp takes a census in the Wairapapa Valley

In his letter to the Government February 9, 1849 (NZ Gazette 1849: 87) he comments on the general status of the Maori population as follows:

It is perhaps, not widely known that in 1848 the Wairarapa valley was seriously being considered by the Government as the location for Edward Gibbon Wakefield's "Church of England Canterbury Settlement". This was a scheme for introducing a slice of English Society into New Zealand. Kemp had a meeting at Huangarua on November 14, 1848, to discuss this with European settlers, notably: Smith, Revans, Bidwill, Tiffin, Donald, Caverhill, Northwood, Tully, and Collins.

A large meeting of Maori chiefs was held to discuss selling all the land in the Wairarapa "at the Central Maori Settlement", within a mile or two of Captain Smith's station", and "the natives began to assemble on Monday the 8th instant [1849]" (NZ Gazette, 1849: 85). For a number of reasons, acquiring the entire Wairarapa valley for the proposed European settlement foundered. What is more interesting in the present context is exactly what was this Central Maori Settlement, and where was it? Kemp does not name it specifically. Was it the Maori village at Huangarua, or the village at Kaupekahinga?

Kemp's diary clears this matter up. On Friday 5th of January 1849 he left for Kaupekahinga. On the 6th he set out for Huangarua and pitched his tent. On the 7th he halted because of bad weather. On the 8th he was at Huangarua preparing his census. On the 9th he wrote a letter stating that the meeting would be delayed because of the bad weather. On the 10th the speeches started in earnest, and carried on until all the Maori left on the 16th of January. So, I can conclude that The Central Maori Settlement was Huangarua. However, exactly where this Maori village was located is, at present, unknown.

Kemp presented his first census to Government, and it was published in the NZ Gazette, dated January 1849 (pages 84-92). This is outlined below. Of considerable interest is his remark that Kaupekahinga is a Strong Pa. The ratio of adults to children is 4.3 which seems very high. Kaikokirikiri is by far the most populous village, followed by Otaraia, Peutangiroa, and Kaupekahinga. Males outnumber females by 1.4 to 1.

The year 1845 saw William Colenso's first trip into the Wairarapa valley. He travelled down the east coast from Napier to Wellington a number of times, and visited Huangarua pa no less than six times:

4 April 1845

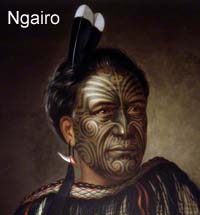

Although village sizes varied from one trip to another, the average size is of considerable interest. On his trip in 1845, Colenso recorded that Omoekau was a village of 30 people, Parikarangaranga 20 people, that Otaraia was deserted, and that there were 100 people at Kaikokirikiri. He noted in his diary that he met the young chief of Huangarua, Ngairo, and that his brother Ngatuere was the chief of Otaraia.

In 1846 when he next visited Otaraia, Ngatuere was building fortifications, since he was expecting an invasion by Te Hapuku, following some dispute between the two of them. Clearly inter-hapu conflict was far from over in the mid-nineteenth century. On this same trip, he notes that there were 200 people at Huangarua.

18 March 1846

5 November 1846

22 May 1848

14 March 1849

15 March 1850

Tacy Kemp visited the Wairarapa four times between October 1848 and mid 1850, and made detailed observations and carried out a census of Maori people, which affirmed Colenso's fears of a declining population. In January 1849 he recorded 780 Maori living in 10 villages in the lower valley, and 6 villages along the coast. In June 1850, this number had declined to only 563 (Bagnall, 1976: 194). His detailed record of how many huts there were, acreage under wheat, maize and potato, number of horses, goats and pigs, and how many people could read and write, etc., makes fascinating reading. It is reminiscent of the Domesday survey of England in 1066 for the detail it reveals of the population at that time.

"His Excellency will be pleased to learn that the tribes who now inhabit the valley and coast (considering that they were but a few years ago amongst some of the most barbarous in the Southern District) have made rapid advancement, and are now to a very great extent in the enjoyment of European comforts. Some are holders of cattle, others of horses and sheep; and in every village it is to be seen the wheat-field, the stack, and mill, and what is still more gratifying, the use of bread is now becoming universal, and is an article of daily consumption".

This is interesting because in his formal census report to Government, there are columns for numbers of sheep, and hand mills, and a zero entry for each village (NZ Gazette 1950: 244).

| Village | Males | Females | Children | Total | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turanganui | 24 | 22 | 14 | 60 | - |

| Peutangiroa | 41 | 24 | 6 | 71 | - |

| Tananui | 15 | 9 | 7 | 31 | - |

| Motiti | 3 | 7 | 5 | 16 | 3 children half-caste |

| Otavaia | 52 | 30 | 12 | 94 | - |

| Kaupekahinga | 29 | 26 | 13 | 68 | Strong Pa |

| Huangarua | 13 | 8 | 3 | 24 | 1 child half-caste |

| Taununa | 6 | 4 | 1 | 11 | - |

| Hurinuiorangi | 14 | 9 | 10 | 33 | - |

| Kaikokiukiu | 89 | 54 | 53 | 196 | - |

| Oroi | 15 | 12 | 0 | 27 | - |

| Awaiti | 8 | 8 | 8 | 24 | - |

| Pahawa | 14 | 14 | 6 | 34 | - |

| Wharaurangi | 12 | 8 | 2 | 22 | - |

| Waipapa | 11 | 10 | 11 | 32 | - |

| Wareama | 16 | 10 | 11 | 37 | - |

| Totals | 363 | 255 | 162 | 780 | - |

Kemp presented his second census to Government, and it was published in the NZ Gazette, dated June 15, 1850 (page 244). The Maori population had fallen from the previous year's 780 to 563. The ratio of adults to children is 4.6 which is higher than the previous year. Males outnumber females by 1.7, which is worse than the previous year. The most populous village is still Kaikokirikiri, followed by Turanganui, Otaraia, and Waihinga/Kaupekahinga. The population of Turanganui has doubled since the previous year. These changes since the show a mobile population. This is specifically commented on by Kemp in his final report to Government thus:

"Another difficulty in connection with the maori[sic] census is this, that the natives are scarcely for many months stationary; and so with regard to their cultivations; it frequently happens that the same individual has cultivations in two or three different parts of the country as his inclination guides him, if the locality is good. The Returns which have been compiled may, however, be considered as a very close approximation..." (NZ Gazette 1851: 240)

| Village | Males | Females | Children | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Te Hawera | 15 | 9 | 5 | 29 |

| Kaikokirikiri | 104 | 54 | 26 | 184 |

| 22 | 17 | 16 | 55 | |

| Huangarua | 33 | 16 | 8 | 57 |

| Waihinga & Kaupekahinga | 19 | 13 | 7 | 39 |

| Otaraia incl. Hikunui & Matiti | 38 | 25 | 12 | 75 |

| Tauanui | - | - | - | - |

| Turanginui | 58 | 14 | 26 | 124 |

| Totals | 289 | 174 | 100 | 563 |

In Kemp's second census he also included agricultural production and livestock figures for Maori villages (NZ Gazette June 15, 1850, page 244). His tabulations record no kumara gardens, and no sheep being kept by villagers. There are no entries for the village at Tauanui, which is hardly surprising since the population recorded above was zero. Four of the villages were receiving considerable income from renting land to European farmers. There is a surprisingly high degree of literacy considering that only 10 years had elapsed since the first European had set foot in the Wairarapa. Most of this may be attributable to the influence of the rapid spread of Christianity. Kemp recorded 437 Maori parishioners, mainly Church of England (404), but also Weslayan (20) an Roman Catholic (13). The average area under cultivation for crops per person is 0.28 acres per person.

| Village | Wheat | Maize | Potatoes | Other Gardens | Tame Pigs | Goats | Rents Received £ |

Read & Write | Huts | Horses | Cattle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Te Hawera | - | - | 7 | - | - | - | - | 6 | - | - | - |

| Kaikokirikiri | 10 | 7 | 34 | 3 | 130 | 3 | 84 | 24 | 20 | 5 | 4 |

| Hurinuiorangi | - | 4 | 10 | 2 | 40 | - | 12 | 8 | 13 | 2 | - |

| Huangarua | - | 3 | 9 | 1 | 36 | - | 88 | 11 | 7 | 9 | 1 |

| Waihinga & Kaupekahinga | 2 | 3 | 7 | 1.5 | 35 | - | 36 | 7 | 11 | 5 | - |

| Otaraia incl. Hikunui & Matiti | - | 5 | 14 | 2 | - | - | - | 9 | 17 | 15 | - |

| Tauanui | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Turanginui | 3 | 10 | 21 | 3 | 72 | - | - | 39 | 17 | 13 | - |

| Totals | 15 | 32 | 102 | 12.5 | 349 | 3 | 588 | 104 | 85 | 49 | 5 |

Some details of a survey of European stations were published in the Dominion newspaper 8 November, 1911 (Volume 5, issue 1280, page 10), and are worth quoting in full as they provide a wonderful insight into the conditions of farms in 1847.

THE CENSUS OF 64 YEARS AGO

Inhabitants of the flourishing Wairarapa of to-day will doubtless be interested in an ancient document which has been placed at our disposal by a well-known Wairarapa resident. The document is a census return of the population of the district 64 years ago and it runs as under:-

Ahiaruke [sic] and Parumuokaka.-Station proprietors, Tiffin and Northwood; men employed 7, women 2, children 1; horses, 4; cattle, 9; sheep, 2750; average cultivation, 5 acres; rent to Natives, £48.

Huangaroa.-Captain Smith; men 8, women 2, children 8; horses, 4; cattle, 90; sheep, 2000; cultivation, 5 acres; rent £24.

Hakeke.-Mr. Morrison; men, 2, women 2; horses, nil; cattle, 160; sheep, nil; cultivation, 1 acre; rent, £16.

Kopungara.- C.R.Bidwill; men 4, women nil, children nil; horses 46; cattle, 195; sheep, 420; cultivation, 4 acres; rent, £32.

Warekaka.-Clifford and Weld; men 7, women nil, children nil; horses, 2; cattle, 13; sheep, 3200; cultivation, 4 acres; rent, £36.

Otarioa.- Gillies; men 7, women 2, children 3; horses, 3; cattle, 60; sheep, nil; cultivation, nil; rent, £12.

Tuhitarata.-McMasters; men 2, women 3, children 1, horses 4; cattle, 120; sheep, nil; cultivation, 1 acre; rent, £13.

Tauanui.-Allom; men 2, women and children, nil; horses, 1; cattle, 180; sheep, 274; cultivation, 1 acre; rent, £25.

Tauranganui North.-Kelly; men 4, women and children, nil; cattle, 60; sheep, nil; cultivation, nil; rent, £12.

Tauranganui South.-Williamson and Drummond; men 4, women 1, children nil; horses, 5; cattle, 370; sheep, nil; cultivation, 3 acres; rent, £12.

Whangamoana.-Russell and Wilson; men 3, women and children nil; horses, 3; cattle, 2; sheep, 1000; cultivation, 2 acres; rent, £12.

Wateranga.-Fitzgerald and Pharazyn; men 2, women 2, children 4; horses, nil; cattle, 12; sheep, 966; cultivation, nil; rent, £12.

Kawa Kawa.-J.P. Russel; men 2, women and children nil; horses, nil; cattle, 62; sheep, 80; cultivation, nil; rent, £24.

Kiriwai.- Cameron; men 2, women and children, nil; horses, nil; cattle, 62; sheep, nil; cultivation, nil; rent £24.

Mangonia East.- Barton; men 3, women and children, nil; horses, nil, cattle, 30; sheep, 1600; cultivation, nil; rent, £24.This makes in all [in 1850] 59 men, 14 women, 19 children. 73 horses, 2365 cattle, 11291 sheep, 26 acres under cultivation, rent £325, and only 15 stations.

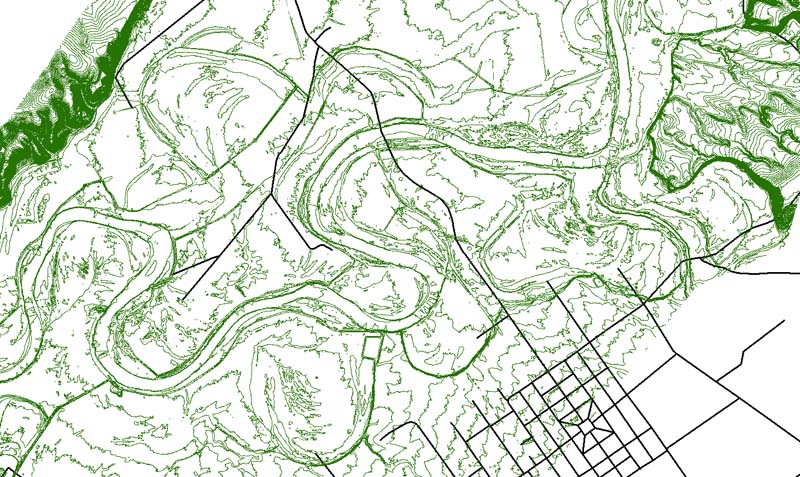

This valuable information is also tabulated in Bagnall (1976: 73) with no indication on its origin. However, the source is made clear by Goldsmith (1996: 11-12) and it turns out to have been reported by Francis Dillon Bell to Edward Gibbon Wakefield (23 March 1847, Great Britain Parliamentary Papers, volume 8, session 570, page 58). In 1847, Bell was commissioned by the New Zealand Company to purchase lands in Wairarapa for the proposed Canterbury Settlement.

Only 10 years had passed since William Dean first set foot in the Wairarapa, and a mere six years since Bidwill brought his 350 Merino sheep around Cape Turakirae into the Wairarapa. Kemp's record above shows rapid and dramatic change for such a short period. As both Kemp and Colenso remarked, these changes had wreaked havoc on the dwindling Maori population. There are considerable discrepancies between the rents paid by these settlers and the recorded rent received by Maori for the same year as recorded by Kent. The ratio of men to women is 4.2, which is far worse than the Maori population (1.4 and 1.7 for the years 1849 and 1850, see above). The average area under cultivation for crops per person is 0.28 acres per person (exactly the same as for the Maori villagers).

Kemp also recorded for posterity the names of the Maori chiefs who had authority over the lands being squatted on by European settlers, and to whom they paid rent for this privilege. It is an interesting facet of history that many of the names of these squatters still resonate among Europeans living in Martinborough today, as descendants of the squatters still live in the district. However, very few modern Europeans will have heard of the names of the chiefs, even though their descendants live here too. The chiefs are still remembered, indeed revered, by present-day Maori. Part of the reason for this lacuna is that these chief's names were not passed on as family names to descendants. Nevertheless, there is an unfortunate culture-historical divide when celebrating the pioneers of the lands surrounding Martinborough.

| Squatters | Native Chiefs | Residence |

|---|---|---|

| Donald's Station | Korow and Ngatuere | Kaikokeriker |

| Wilson's | Raniera | Kaikokeriker |

| Tiffin's | Hamuera | Kaikokeriker |

| Morrison's | Pirika | Taununa |

| Captain Smith's | Ngairo | Huangarua |

| Bidwill | Manihera | Otaraia |

| Clifford | Te Tati | Turanganui |

| Gillis & Tankersley | Ngatuere & Manihere | Otaraia |

| McMaster | Poneke | (Matiti) |

| Tully | Te Hamaiwaho | (Peretangiroa) |

| Kelly | Tamihana | Turanganui |

| Drummond | Raniera | Turanganui |

| Rupete | Hamahona | Turanganui |

| Cameron | Poneke | Matiti |

| Pharazan | Maraia | Peutangaroa |

| Burling | Manihera | Otaraia |

| Cameron's | Hoera | Pahawa |

| Guthrie | Potangoroa | Castle Point |

| Northwood | Te Hapuku | Ahuriri |

Kemp's final report to Government on the Wairarapa District is dated 15 April 1850 (NZ Gazette 1851: 237 ff.). In this he provided the Government with a summary sketch of each of the Maori settlements in the Wairarapa. Those from Martinborough southwards are described thus:

32nd Settlement - Huangarua

About 15 miles from Hurinuiorangi, is the residence of the chief Ngairo, and is, I should think, the most central station in the valley. It was at this village that the negotiations for the purchase of the land were carried on last year, and is situated on the bank of the Ruamahanga. The change that has taken place since that time for the worse is almost incredible. Several deaths had taken place, others I saw in a dying state, huts decaying and destroyed, and the whole a complete wreck. Nor is it likely ever to recover itself. Ngairo urged the selling of the land, but his expectations in the shape of payments were too large. He has been a very turbulent native, and used to be held in great terror by many of his own people. His intercourse with the Europeans has made him much more quiet and better disposed. They cultivate in small patches, but principally near the settlers to ensure a market. I observed a great deficiency in the wheat crop compared with last year. This is also the case in the Manawatu, where the flax has monopolised the trade. Total native population, 57.

33rd Settlement - Waihinga and Kaupekahinga

Are two small villages or plantation grounds belonging to Huangarua and Otaraia, situated on the banks of the Ruamahunga, about midway between Captain Smith's and Mr. Bidwill's stations: the soil here is exceedingly good, and last year produced some of the finest wheat I ever saw; a few stacks still remain. The population is very small, only 39.

34th Settlement - Otaraia

Is situated about 12 miles from Huangarua, and is the Pa built about four years ago when the celebrated chief "Te Hapuku" threatened a hostile descent upon the natives of the valley in consequence of some insult offered by them to his son: he came down from Hawke's Bay, but returned without doing any mischief. The Wairarapa natives were, however, obliged to make an atonenent for the insult, and Ngairo was deputed to be the bearer of a considerable sum of money, together with some other articles of value, and to arrange a reconciliation which he accomplished. Ngatuere, Manihera, and William King, are the principal men of this Pa, and were the strongest opposers to the selling of the land. The Pa is now nearly a wreck, and since the peace with Te Hapuku, they feel more security in living in the plantation grounds, which are within a short distance of the Pa. Population, 75.

35th Settlement - Tauanui

Will soon be deserted - natives remove to Hurinuiorangi.

36th Settlement - Peretanginoa

Residence of Te Hamaiwhao; remove also to the new Pa at Hurinuiorangi.

37th Settlement - Turanganui

Situated at the lower end of the lake, distant 12 miles from Otaraia; is the residence of Simon Peter, the principal chief of the Ngaitahu, who is a peaceable old man. Turanganui was one of the earliest villages formed after the natives returned from Nukutaurua, or East Cape, under the sanction and conduct of the late Te Wharepouri. The first party, I believe, settled at Te Kopi, a small but exposed bay on the sea coast, having but very little good land in the neighbourhood. When, however, the Europeans began to settle in the valley, and confidence became restored, the Ngaitahu (a subdivision of Ngatikahuhunu's) ultimately took possession of such parts of the valley as were within a convenient reach of the settlers - hence arises the comparatively few persons residing in each of the villages, as will be noticed by the annexed Returns.

At Turanganui a neat weather board church is in course of erection. The Pa is in tolerably good order, and the crops, which are small, promise well. Turanganui is a favourite spot for eel fishing; the lake being closed at certain seasons, great quantities are caught and dried for the winter.

The natives of Wairarapa are descended from their ancestor Kahuhuhunu, who is supposed to have peopled the whole of the coast from thence to the East Cape or Poverty Bay. They are a very powerful tribe, although in many parts uncivilized, particularly those subdivisions which reside between Wairarapa and Hawke's Bay; those inhabiting the Wairarapa, considering the intercourse they have had with white people are not much improved. They are far from being industrious, or anxious to obtain employment; and this is to be accounted for by the comparatively easy manner in which they obtain European comforts through a considerable sum of money annually paid to them in the shape of rents for the use of the land. Population, 124.

Kemp recommends Ngairo to the Government

As an instance of this, he did not hesitate for a moment to allow the natives to assemble at his village, and the consequence was that a large quantity of his provisions, were consumed. On one day alone near (20) twenty pigs were killed and distributed to the different tribes

assembled. It is on this account that I take the liberty of submitting for his Excellency's consideration that the present would be a fitting opportunity to show that the Government were willing to reward good conduct, and, generally speaking, I think it would have a good effect if a suitable return was made to this Chief. It might induce others to folIow his example,

and to co-operate with the officers of Government in completing the purchase at a future time.

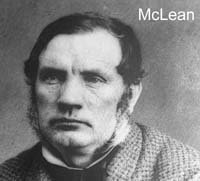

Lindauer (1839 to 1926) came to New Zealand in 1874, and many of his Maori portraits were exhibited in 1886. He settled in

Woodville in 1887. Colenso

describes Ngairo as a "young chief" when he met him at Huangarua in

1845. At the celebrated Kingitanga feast/meeting held at Waihinga in 1859 (more on this below)

he is described in the newspaper as "the good hearted old Ngairo". If

Ngairo was between say 25 and 35 when Colenso met him that suggests he

was born about 1810-1820. If Lindauer painted him in say 1885, Ngairo

would have to be about 65 to 75 years old. The man in the painting

looks a lot younger than that. Ngairo is variously named as Ngairo Takatakaputea, Ngairo Apuroa, and Ngairo Rakai Hikuroa.

The Ruamahanga river has a strong influence on Maori and European activities

Before leaving Kemp's reports on the Wairarapa, it will have been noticed that he refers to a chief called Ngairo several times. At the conclusion of his negotiations with Wairarapa Maori he felt obliged to write a formal letter acknowledging Ngairo's help. The letter was published in the NZ Gazette 1849, page 88

(Clickhereto see the original), and is transcribed below:

Before leaving Kemp's reports on the Wairarapa, it will have been noticed that he refers to a chief called Ngairo several times. At the conclusion of his negotiations with Wairarapa Maori he felt obliged to write a formal letter acknowledging Ngairo's help. The letter was published in the NZ Gazette 1849, page 88

(Clickhereto see the original), and is transcribed below:

Wellington, February 15, 1849

We are fortunate that Ngairo's original letter has been saved for posterity,

Clickhereto see it, andhere to see the hand-written translation of it. Lindauer made two paintings of Ngairo, one is held in the

Pitt Rivers Museum, and the other, much darker version, is in the Dunedin Public Art Gallery. It is not known whether Lindauer painted Ngairo in person or from a photo. He appears to be a fairly young man in the painting, which is not easy to reconcile with the little we can deduce about the date of the painting.

SIR, I Have the honour to enclose a letter with its translation from the Chief Ngano [sic] addressed to his Excellency the Lieutenant-Governor. The writer of this letter is one of the principal men of the "Wairarapa", and is favourably inclined to sell, and throughout the negotiation did me the greatest service.

I have, &c.

(Signed) H. TACY KEMP

F. ORMOND, Esq.,

&c. &c.

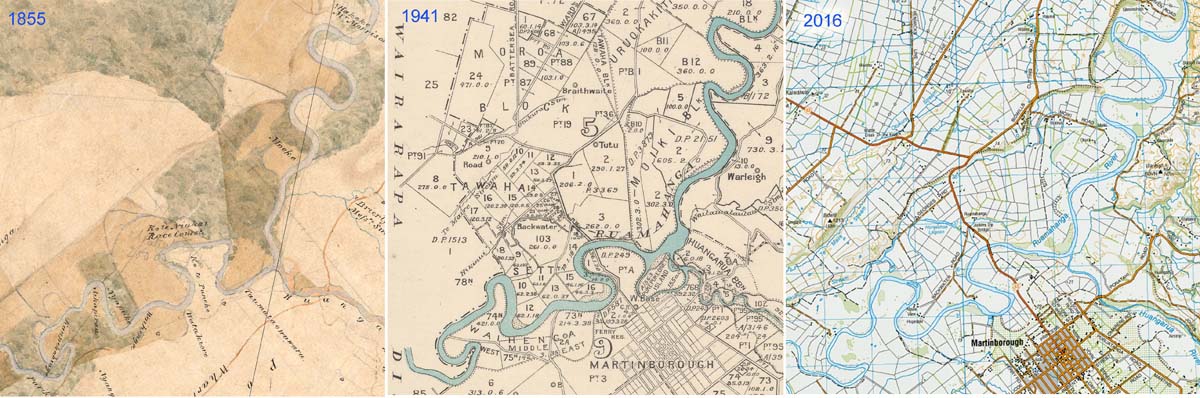

The map below was made in 1855 (the year of the massive Wellington earthquake), and considerable changes have occurred in the interval. Just below the junction of the Huangarua and Ruamahanga rivers, where present-day Martinborough is located, the area is named as Taumata o wawuru (the resting place of Wawuru), and several other Maori names are shown nearby which feature on later maps, such as Waihinga, Ko Te Puneke, Watakiore, and Ngapuke. It is noticeable that the Huangarua pa is not marked. There are two European paths now. The second one branches off just north of Wharekaka homestead and travels close to the Ruamahanga, almost as far as Ngapuke. Otaraia pa is marked close to where Mr Gillies resides.

The first thing that will be noticed about the above 1855 map by anyone from Martinborough observing it, is that the Ruamahanga River seems to be in the wrong place! This is made clearer with the image below which shows three snapshots of the river, dated at 1855, 1941, and 2016. In the earliest map, the Ruamahanga River flowed along the bottom of what is known today as Tod's Cutting and around past the area where the timber mill once was. From there, the Huangarua river joined it. The cadastral map made in 1941 shows that the Ruamahanga had broken through the land near where the present-day Ruamahanga Bridge is, and encircled an island of land known as Pukepukeonetea (155 acres). In another map dating to 1882 (DP-249), the flow of water running along the bottom of Tod's cutting is labelled as the Huangarua River, so it is clear that the Ruamahanga had broken through the-low lying land to the north by that time. The final map below on the right shows the situation today. The separate island surrounded by water has disappeared. The development of stop banks along the course of the Ruamahanga encourages it to keep flowing along a single course.

The merging of the Huangarua and Ruamahanga rivers has had a long and complicated history.

The merging of the Huangarua and Ruamahanga rivers has had a long and complicated history.

In point of fact, over thousands of years the Ruamahanga River has moved all over the flat flood plane of the Wairarapa valley. It is a typical example of what is technically an Old River, in the sense that it meanders around in large loops, occasionally breaking through a loop to leave behind an oxbow pond. The image below shows how complex the history of the Ruamahanga River really is. There are old loops and oxbows scattered all over the area between Tod's Cutting and Bidwill's Cutting. Such a remarkable image is made possible with the advent of LiDAR surveying (Light Detection and Ranging) where a pulsed laser is pointed at the ground from an aircraft, and the reflected pulses detected so that the distance can be calculated very accurately. The image below shows contours at 1m interval (Courtesy of Geoff Lewis, Greater Wellington).

The Ruamahanga River has twisted and turned acrtoss the flat land between Bidwill's and Tod's Cuttings over millennia, leaving behind its imprint on the landscape. The green lines are 1m contours from LiDAR survey. Note only a few times does a contour cross the river channel, which shows the low profile of the river.

Society in Transition 1850 to 1872

The Alienation of Maori Ownership of Wairarapa

Until 1846, Maori had been doing very well in the Wairarapa, with a few Europeans living in their midst. These were the squatters, mentioned above, grazing sheep and cattle on increasingly established stations. For this privilege, the squatters paid rent to the appropriate chief who held Mana over the land.

In the case of the land near where Martinborough would eventually be established this was Chief Ngairo, and the squatter was Captain William Mein Smith (a South African who became the Surveyor General of the New Zealand Company in 1839). According to Bell's report in 1847 Smith paid £28 per year rent. Kemp's report of 1850 shows the rent being paid to Ngairo was then £88 per year. The curious difference between these two reports remains unexplained. The important point is that once Europeans came into the valley there was quickly established a system of renting land which was mutually beneficial to Maori and Pakeha alike. However, as Goldsmith has succinctly pointed out:

On 21 February 1846, Governor Grey waived the Crown pre-emption on the purchase of land in Wairarapa in favour of the New Zealand Company (ibid.: page 8).

"Betweeen 22 June 1853 and 18 January 1854, the 'deadlock' was broken in a spectacular way, and about 1,500,000 acres of Wairarapa land was sold by local Maori in a series of 41 deeds" (ibid.: 19). The New Munster Executive Council became involved, and Donald McLean was given sweeping legal powers to deal with anyone standing in the way of progress in acquiring land. He negotiated sales on behalf of the NZ Company. In addition, in August 1853, Governor George Grey made a personal visit to the Wairarapa to take an active role and met squatters and Maori owners and this resulted in a flood of sales of small homestead blocks of squatters and large rented blocks. The most important were:

The backdrop to this was Governor Grey's threatening letter which he sent to Wairarapa Maori in March 1847:

William Nicholas Searancke was appointed District Land Purchase Commissioner by McLean in 1858. He was beset by Maori airing their grievances, and wrote to McLean (28 May, 1858):

Fortunately, there was no armed conflict in the Wairarapa during the New Zealand wars. Some Wairarapa Maori fought alongside Taranaki forces, selling land to buy arms. Sympathy for Maori war aims led many to support Maori sovereignty and the Kingitanga movement. For example, Ngairo and some Wairarapa men joined in the

hostilities on the west coast.

Wardell (the Wairarapa Resident Magistrate) in his report 'On the state of Natives' to Government in 1868 summarised this as follows:

Kingitanga and Waihinga: The great Feast, 1859

The meeting at the Waihinga village must have been well advertised in advance for so many people to have attended, but I have not been able to find information on exactly how word was spread beforehand. One of the newspaper reports (item 5 above) is transcribed below.

The dinner was laid out in a large house, built expressly for the occasion, about seventy feet long by twenty feet wide; three times were the tables loaded with provisions by the hospitable entertainers, and cleared by the natives present. About two o'clock the Europeans were invited to sit down, and I have the greatest pleasure in bearing witness to the caide mille failtha [Céad Míle Fáilte, is Irish Celtic, meaning a hundred thousand welcomes] of the entertainers to their guests, the unbounded hospitality, the admirable arrangements, not to be surpassed, and the general attention which they received from their hosts, who acted as waiters on the occasion.

The feast feast being over, the tables were cleared away, and the Europeans were invited in to listen to the speeches, when the object of the meeting was made known, to get up an agitation throughout the valley in support of the Maori King movement, and the Land League; and to aid and support this agitation Wi Tako had been invited, in order that he might, by his ability and eloquence, convince the wavering. Speeches were made opening the matter, tending to point out the connection between Providence and all nations, including the Maories; and, secondly, between the Queen and her European subjects and natives, questioning the right of the Queen to look upon the Maories as subjects, and gradually pointing out that the allegiance paid by Maories must naturally be to a Maori King, and not to the Queen.

At this point of the proceedings one of the most distinguished of the European guests, considering a little refreshment necessary, lighted his pipe, which so aroused the wrath of that great bounce, Ngatuere Tawhao (who considered it an insult to the meeting), that an adjournment, by universal consent, took place for the same purpose, and the proceedings for this day ended in smoke.

On the following day a few only of the Europeans attended, when the proceedings were resumed; but not with that degree of energy and animation formerly so characteristic of the Maori. Speeches were much of the same character; natives strutted and looked big or graceful, as the case might be; but it was patent to all conversant with them and their former ways, that, so far as the Wairarapa is concerned, the glory has departed from Israel [the old ways were gone forever].

The Queen's authority has been strongly supported by that old, tried, and true friend of all Europeans in the valley, Te Manihera, not only on these occasions, but on every other; he and a large party of his friends opposed by unanswerable argument the movement in the valley where the lands are nearly all in the hands of the Government.

The natives still continue their korero, but, owing to the heavy rain and floods, I have not been able to hear of any particulars.

The meeting, as a matter of political importance may be considered a failure; some (perhaps the larger half of the natives in the valley) have, I believe, declared that they will have faith in a Maori king so soon as the benefits to be derived are made visible to them ; but, as this is rather a difficult matter, their faith is not likely to be sorely tried. - lndependent".

Moreover, the chief Ngairo (described as the good-hearted old Ngairo) was responsible for erecting a Wharenui especially for the occasion. This is described as 60 ft long, and 13ft wide, with boards for sides, and a bark roof. The front was ornamented with "superb Maori carvings, well painted and decorated with the brightest plumes of the Huia, Pigeon, and Tui; and surmounted with the effigy of a maori [sic] chief, elaborately tatooed, and holding in his upraised hand the badge of chieftainship - the Meremere club" (Newspaper item 1 above). In Item 2, the opening comment is this:

Unfortunately, the newspaper did not publish the sketch. It would be wonderful to have some idea of the carvings on the outside of the wharenui.

There was an interesting sequel to this great event which took place 45 years later. The Maori newspaper, Te Puke ki Hikurangi featured an article about the meeting. This newspaper initially reported on the activities of the Kotahitanga (Maori parliament movement), but later branched out to cover religious and social issues. It ran from 1897-1900, 1901-1906, and 1911-1913 and was based at Papawai, near Greytown. The article about the meeting at Waihinga appeared in Volume 5(21) of the newspaper, on 6 August 1904 (Clickhereto see the relevant page of the newspaper).

The content is translated below (courtesy of Professor Ray Harlow):

On the day of the beginning of the hui, the hapu of the marae welcomed Witako and his people. The speeches of the chiefs of the marae were about promoting the activities of the King. These are the words of the haka [haka words not translated]

The iwi assembled at the marae, but nothing was found as a slogan, so Hikawera (his real name at that time was Wiremu Mahupuku) and Heremaia Tamaihotua set about seeking a focus for the hui. They proposed to the assembly te Herenga [the binding] and te Wetekanga [the untying]. The meaning of te Herenga was that the people of Waiararapa should maintain the mana of the King, secondly, Faith, that the people of Waiararapa should adhere to the mana of God, thirdly, the maintenance of peace, reconciliation, and aroha with Faith as the basis for all these attitudes.

After this explanation of the word, te Wetekanga was laid out, the meaning of this word is that the authority of the Government should be 'untied' from the Maori people, that no lands should be let go to the Government, with other policies about land. When this explanation was made, the people of Wairarapa became divided; some of the chiefs sided with the Government, namely, Te Raniera Teihooterangi. Hemi te Miha-O-Te-Rangi. Tamaihikoia, with their hapu, Rakaiwhakairi, with the small hapu under him, these hapu were from Ruamahanga, including Ngati Moe, Ngati Kahukurawhitia, Ngati Muretu. These are the names [of their chiefs]:

Te Manihera Rangitakaiwaho, Wiremu Kiingi Tutepakihirangi, Ngatuere Tawhirimatea, Ihaka Te Moe.

In the direction of Kauru kia Hamua. Ihaia Whakamairu, Te Retimana te Korou.

To the sea,to Ngati Rongomaiaiaa, to Ngati Maahu, te Wereta Kawekairangi, these were the chiefs who turned to the Government side of Wairarapa, away from the King.

The hapu which adhered to the King was Ngati Hikawera, until 1883. The chiefs were Ngairo Takatakaputea, Wiremu Mahupuku, Tamahau Mahupuku, Karauria Ngawhara, with their young man Heremaia Tamaihotua, who was their ally at the time, when he was still young.

Nonetheless he has retained some record of what was said [at the hui]

Let the account of the hui be a memorial to him.

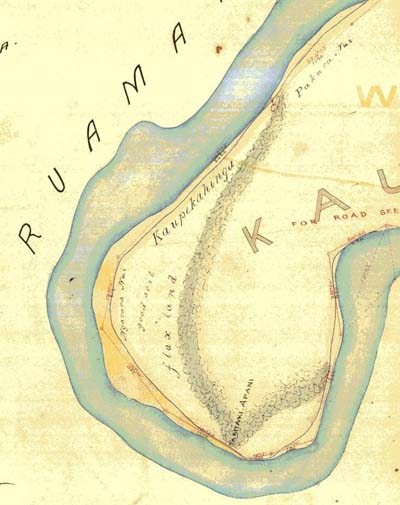

On the full version of the map it will observed that there were was a 'native track' leading to Kaupekahinga from the surveyed road. There was also a ford across the river close to the Waihinga village, second ford next to Field's Public House, on land named named Otuweroha, and a ferry further north at Te Uruhinga.

Clickhereto see the whole map.

And, clickhereto see the location of these two villages vis-a-vis Martinborough.

The Township of Wharekaka/Bairdsville/Waihinga Established in 1872

Wharekaka Town was not the only name that was proposed for the budding township. An item appeared in a newspaper which describes the adventures that a group of pastors had on their way across the Ruamahanga in a canoe to get to a special event to open a new church:

There are numerous later annotations on this plan, and it would be most interesting to follow some of them up. For example, when and why was Bismark Street renamed French Street, etc.

Requests to LINZ (Land Information New Zaland) for such information requires clear unequivocal document name or filename so it can be found at $15 for each request. For example, the large writing "Plan 24" would not be adequate without additional information. Its correct name is Deed Plan 24. I asked for the correct way to specify some of the file reference numbers/names on this map and was told the following:

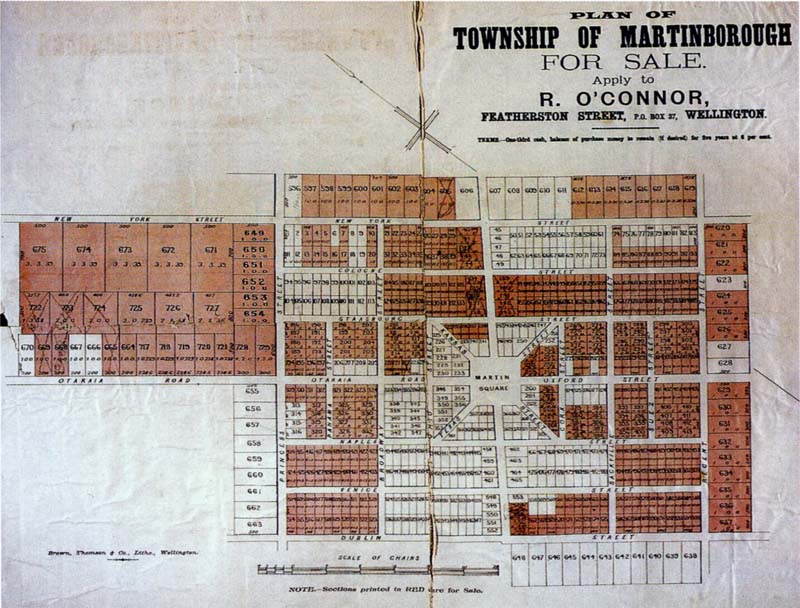

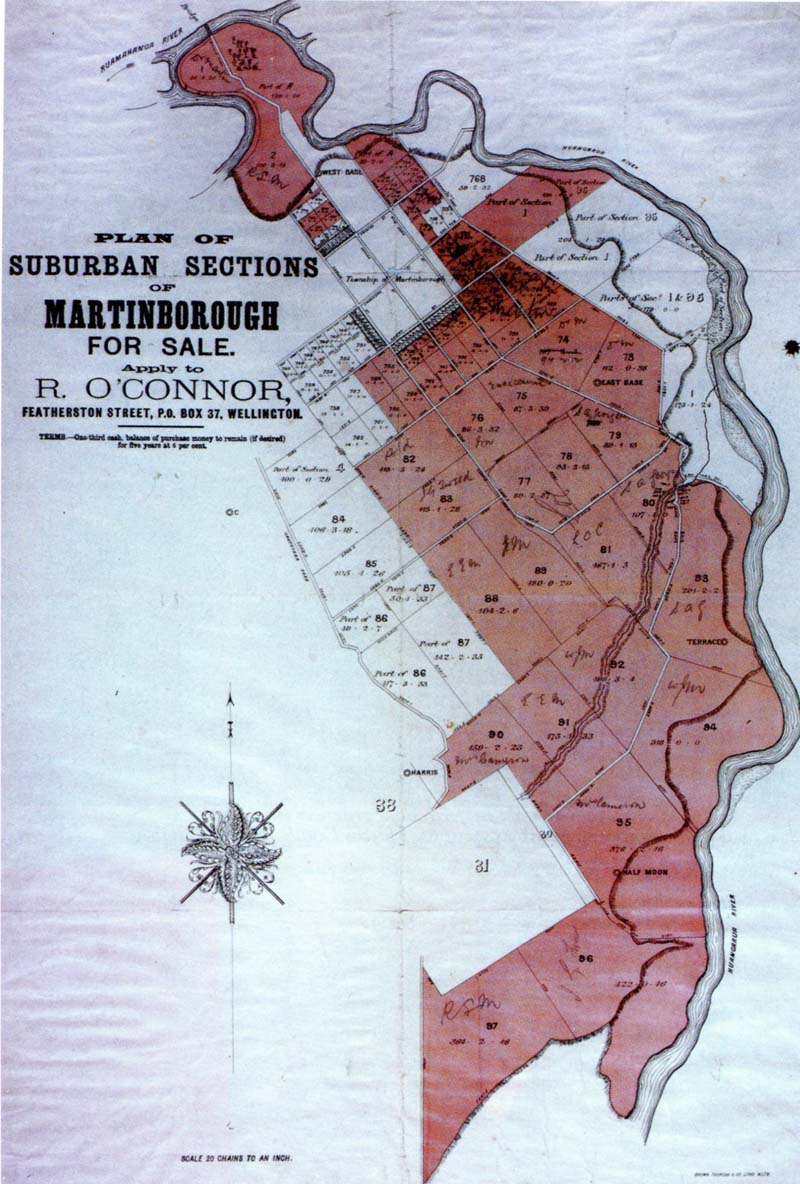

Martinborough Township Established 1879

The township of Martinborough was first submitted. No bids were offered for sections 1 to 193. Sections 191 to 197, on the Otaraia road, were knocked down to the Hon. Colonel Brett for £5 3s each, and 198 to 201 to Mr. Sheehan for the same amount. Other sections were sold for about the same price, the highest bid being £5 15s until a corner section abutting on Kansas and Martin Square, which was knocked down to Mr. Peacock for £ll. Two adjoining sections were sold to Mr. H. D. Bell for £15 each.

After other lots in the township had been offered with indifferent success, the sale of agricultural holdings was proceeded with, but there were very few buyers - the tightness of money evidently being very generally felt. A few holdings were disposed of prior to our going to press at prices ranging from about £3 10s to £4 10s an acre".

The description of what follows relies to a great extent on the intensive research and review carried out for the Waitangi Tribunal by Paul Goldsmith (Goldsmith, 1996).

The description of what follows relies to a great extent on the intensive research and review carried out for the Waitangi Tribunal by Paul Goldsmith (Goldsmith, 1996).

"The prospect of Europeans coming, settling, working, and improving the land, while Maori sat back and enjoyed an ever-increasing income from that work, presumably to become a wealthy indigenous aristocracy, was unpalatable to many" (ibid.: 7).

Colenso, with clear foresight of looming problems, advised Wairarapa Maori:

1. Not to sell their lands in the Wairarapa

However, in what can only be described as one of the most iniquitous acts ever, The Native Land Purchase Ordinance was passed by Government in 1846. This prohibited private leasing arrangements, and reaffirmed the Crown's right of pre-emption over selling land. Goldsmith described this Government edict thus:

2: Not to lease them beyond 21 years

3: Not to lease the whole of their good grazing land

4: Not to lease it in very large blocks ... to one person

5: To make deliberate choices of the person to whom they would let it...

(Colenso, Journal, 18 September 1846)

"It would force Maori to decide between maintaining interaction with Pakeha on the basis of selling, or retaining their lands but also embracing economic and social isolation" (ibid.: 6-7).

Since Maori could no longer lease land for income, they were put in the position of having to sell land to the Crown who would then sell it on to Europeans.

Between Feb 1847 and Jan 1849 agents of the NZ Company were in the Wairarapa three times dealing with Maori for the purchase of lands. Francis Dillon Bell was commissioned by the NZ Company to purchase lands for the Canterbury settlement. This was followed by Kemp's attempts, including setting aside Reserves for Maori.

Between Feb 1847 and Jan 1849 agents of the NZ Company were in the Wairarapa three times dealing with Maori for the purchase of lands. Francis Dillon Bell was commissioned by the NZ Company to purchase lands for the Canterbury settlement. This was followed by Kemp's attempts, including setting aside Reserves for Maori.

"By 1850 in Wairarapa the situation was complex. On one hand, there was a group of Maori who seemed willing to sell a lot of land either very cheaply with a promise of extensive settlement, or for a larger price without such a promise. There was another group who vehemently resisted the prospect of sale" (Goldsmith, ibid.: 17).

Western Lake Block 200,000 acres,

Eastern Large Block 120,000 acres,

Tuhitarata Block 40,000 acres.

Tauherenikau No 4 Block 430,000 acres.

Plus others along the coast and further north.

All the sales are documented in Turton's "Maori Deeds". The Rev Henry Hanson Turton, was the special commissioner to the Native Minister, and compiled the deeds of sale (photo, courtesy of Puke Ariki). There are considerable errors in estimating the areas of land sold in the Wairarapa, but it appears that about 1.5 million acres were sold and after 1854 there weere only 0.5 million acres left in Maori hands. Wairarapa Maori received £23,547 of which £14,690 was paid when the deed was signed. The rest was to be paid in instalments. In addition, on nine of the largest purchases, Maori were to receive the Wairarapa 5 percent (that is, in theory, 5% of the amount the Government received when sold on to European farmers). This became a complex problem and was followed by numerous disputes.

These sales took place amongst a background of both inducements (possible advantages of settlers coming to the Wairarapa when they bought land from the Government) and threats (inability to lease land in future, and the prospects of no settlers ever coming).

All the sales are documented in Turton's "Maori Deeds". The Rev Henry Hanson Turton, was the special commissioner to the Native Minister, and compiled the deeds of sale (photo, courtesy of Puke Ariki). There are considerable errors in estimating the areas of land sold in the Wairarapa, but it appears that about 1.5 million acres were sold and after 1854 there weere only 0.5 million acres left in Maori hands. Wairarapa Maori received £23,547 of which £14,690 was paid when the deed was signed. The rest was to be paid in instalments. In addition, on nine of the largest purchases, Maori were to receive the Wairarapa 5 percent (that is, in theory, 5% of the amount the Government received when sold on to European farmers). This became a complex problem and was followed by numerous disputes.

These sales took place amongst a background of both inducements (possible advantages of settlers coming to the Wairarapa when they bought land from the Government) and threats (inability to lease land in future, and the prospects of no settlers ever coming).

"if you will not conclude such an arrangement [sell], then I shall desire the Europeans to depart from your lands, and shall put an end to the arrangements at present existing between you and them" (ibid.: 12).

The upshot of this was that the Maori owners sold three quarters of their land (1.5 million acres, retaining 0.5 million acres). But from 1854 to 1865, one third of the remaining land was alienated through Crown purchases. As soon as the purchase agreements were signed, numerous problems emerged. Many of these resulted from inadequate surveys of exactly what was sold, resulting in disputes. McLean came back for a second round of "mopping up" purchases 1854-55. Fewer and fewer signatures appeared on the deeds, resulting in disputes on who had the power to sell. All of this resulted in a deluge of problems.

The upshot of this was that the Maori owners sold three quarters of their land (1.5 million acres, retaining 0.5 million acres). But from 1854 to 1865, one third of the remaining land was alienated through Crown purchases. As soon as the purchase agreements were signed, numerous problems emerged. Many of these resulted from inadequate surveys of exactly what was sold, resulting in disputes. McLean came back for a second round of "mopping up" purchases 1854-55. Fewer and fewer signatures appeared on the deeds, resulting in disputes on who had the power to sell. All of this resulted in a deluge of problems.

"A more unmitigated set of Scoundrels than your Wairarapa Pets it never was my fortune or misfortune to meet what with disputed boundaries of blocks & of reserves and claims for payment over again of Land sold & settled years ago I am almost crazy the fact is this they are fearfully hard up and are now trying it on with me to raise the wind by any means" (ibid.: 62).

Maori and Europeans at War 1860s

Until recently this conflict was known as the Maori Wars, but following the historian James Belich, is now called the New Zealand Wars. The conflicts were initially triggered by tensions over disputed land purchases, but escalated dramatically in 1860 when the Government became convinced that it was faced with united opposition to further land sales, and a refusal to acknowledge Crown sovereignty. Thousands of British troops mounted a campaign to overpower the Kingitanga (Maori King) movement, and to continue to acquire land for British settlers. At the peak of hostilities in the 1860s there were 18,000 British troops pitched against 4,000 Maori warriors. The first major conflict took place in 1843 at Wairau in the South island, followed by Wellington, Wanganui, North Taranaki, Waikato, Tauranga, South Taranaki, East Coast, lasting until 1872.

"In June 1865, Ngairo, accompanied by Wi Waka, and a party of about twenty, at the request of Te Ua and Wi Hapi, left this district for the scene of hostilities on the West Coast... In March 1866 Wi Waka and some others of those who had accompanied Ngairo to the West Coast returned, after having been engaged with the troops. In order to protect them from apprehension as rebels against the Queen's forces a very strong position at Kohikutiu was fortified. The erection of this fortification, and a report that Ngairo was about to return with a large body of men, caused new excitement, which was quieted by Waka surrendering himself in July, when, after an interview with the Hon. the Minister for Defence (Colonel Haultain), he was permitted to take the oath of allegiance, and return to the district. Ngairo, finding that his forerunner Waka had been pardoned, returned on the 15th September, accompanied by Wi Hapi, of Ngatiraukawa, and eighty followers... [on] the 25th of March 1867, when Ngairo surrended himself, and at an interview with His Excellency the Governor was allowed to take the oath of allegience" (AJHR 1868, A-4: 35).

In the same report, Wardell noted that 10 Maori men had been killed fighting with the rebels on the West Coast, and he gave his estimate of the Maori population in the Wairarapa in 1868 as:

Males 350

This is only a modest increase since Kemp's 1850 census of 289 males, 174 females, and 100 children, total 563. There is still a shortage of women in 1868, but the percentage of children has risen from 18% to 29%. His final remarks reveal a demolarised state of Maori society in the Wairarapa.

Females 250

Children 250

Total 850

"Their social habits are, in my opinion, of a lower character than when in a more savage state; they have not a great deal of the energy which they formerly displayed, and have acquired little else than the vices of civilisation" (ibid.: 35).

On the 31st of August 1859 a remarkable event took place at a small Maori village known as Waihinga, on the eastern side of the Ruamahanga River, 2.9 km as the crow flies from the present-day Martinborough Square. It was reported in five different newspapers. One of them even reported it twice in the same issue. In order of appearance, these were:

1: MAORI FEAST AT THE WAIRARAPA.

Wellington Independent, Volume XV, Issue 1362, 9 Sept 1859, page 3

2: ORIGINAL CORRESPONDENCE. WAIRARAPA.

Wellington Independent, Volume XV, Issue 1362, 9 Sept 1859, page 5

3: WELLINGTON.

The Colonist, Volume II, Issue 201, 23 Sept 1859, page 2

4: WELLINGTON.

Taranaki Herald, Volume VIII, Issue 373, 24 Sept 1859, page 3

5: THE MAORI BANQUET IN THE WAIRARAPA-VALLEY.

Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle, Volume XVIII, Issue 77, 24 Sept 1859, page 2

6: THE MAORI KING MOVEMENT.

Wellington Independent, Volume XV, Issue 1367, 30 September 1859, page 5

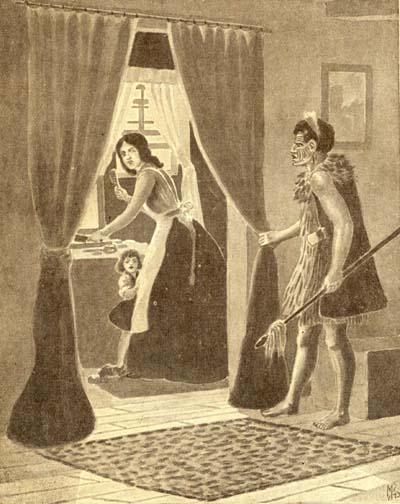

Clearly, this was considered a meeting of some importance, and the title of the last mentioned item gives the reason why. Tensions between Maori and Europeans in New Zealand were at fever pitch in 1859, and the agenda of this meeting would have been alarming to residents. The artist's impression to the left by A.H. Messenger dramatically illustrates the disconcertingly close scrutiny which Europeans were under during the years of conflict, and their fear of worse things to come (Messenger, 1943).

Clearly, this was considered a meeting of some importance, and the title of the last mentioned item gives the reason why. Tensions between Maori and Europeans in New Zealand were at fever pitch in 1859, and the agenda of this meeting would have been alarming to residents. The artist's impression to the left by A.H. Messenger dramatically illustrates the disconcertingly close scrutiny which Europeans were under during the years of conflict, and their fear of worse things to come (Messenger, 1943).

THE MAORI BANQUET IN THE WAIRARAPA-VALLEY.

"On Wednesday, the 31st August, a large number of natives (about 400) met at Te Waihinga settlement, in the Wairarapa valley, by special invitation, to a feast. About 300 were natives of the valley and East Coast, and the remainder consisted of Wi Tako, some of his Hutt followers, and about twenty natives from the West Coast; all the Europeans in the valley were invited, of whom, including Captain Smith and family, Mr. Gillies and family, the Rev. Messrs. Ronaldson and Mason. About ninety attended.

It is interesting that the several newspaper reports present somewhat different tones of the character of this meeting, and I will leave it to the interested reader to examine each for themselves by perusing Papers Past. Clearly a great deal of food was consumed, one report listing 'ten fine pigs, three bullocks and a great consumption of other eatables'. The tables were covered with clean white cloths, and decorated with flowers. The first day was taken up with speeches, which carried on most of that night, and the second day was largely devoted to feasting. The meeting closed on the third day.

It is interesting that the several newspaper reports present somewhat different tones of the character of this meeting, and I will leave it to the interested reader to examine each for themselves by perusing Papers Past. Clearly a great deal of food was consumed, one report listing 'ten fine pigs, three bullocks and a great consumption of other eatables'. The tables were covered with clean white cloths, and decorated with flowers. The first day was taken up with speeches, which carried on most of that night, and the second day was largely devoted to feasting. The meeting closed on the third day.

"To the Editor of the Wellington Independent, Sir, The above rough pen and ink sketch will enable you to form some idea of the building erected by the Maories at the Waihinga, to accommodate the visitors".

This topic is from the year 1859. In that year Ngairo and Matiaha Mokai decided to build a house to further the cause of the Kiingitanga which was being founded in the Waikato. Their plan was agreed to by their hapu, and the house was built and named Aotea. The marae was named Rongotaketake, and the place where the house stood was te Waihinga Matenepara [Martinborough], Wairarapa. On completion of the house all the hapu of Wairarapa assembled at the marae, and initiated a project to invite all the iwi of the country to attend the marae. This was agreed and the invitation went to the iwi of the country.

This contains important new information. Both the marae and the wharenui have names. This is hardly surprising given the amount of work that had gone into its construction, including all the carvings. What is surprising is that there is no mention of these names in any of the newspapers in 1859.

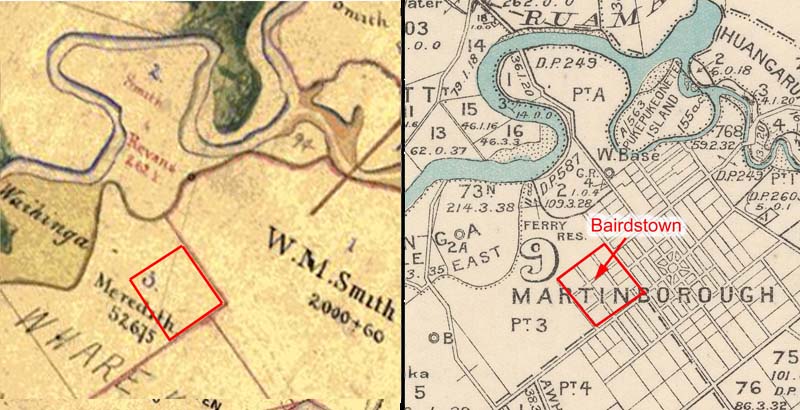

These two images show the presence of the two Maori villages, Kaupekahinga and Waihinga on the eastern bank of the Ruamahanga River. They are enlarged portions of a map, WD-3077, dated 24 August 1867, and signed by Thomas H Smith, who was a survey cadet for the New Zealand Company. It would appear that by 1867, Maori were only occupying houses at Waihinga, as no houses are shown at Kaupekahinga. I assume the large building shown at Waihinga is the wharenui, Rongotaketake.

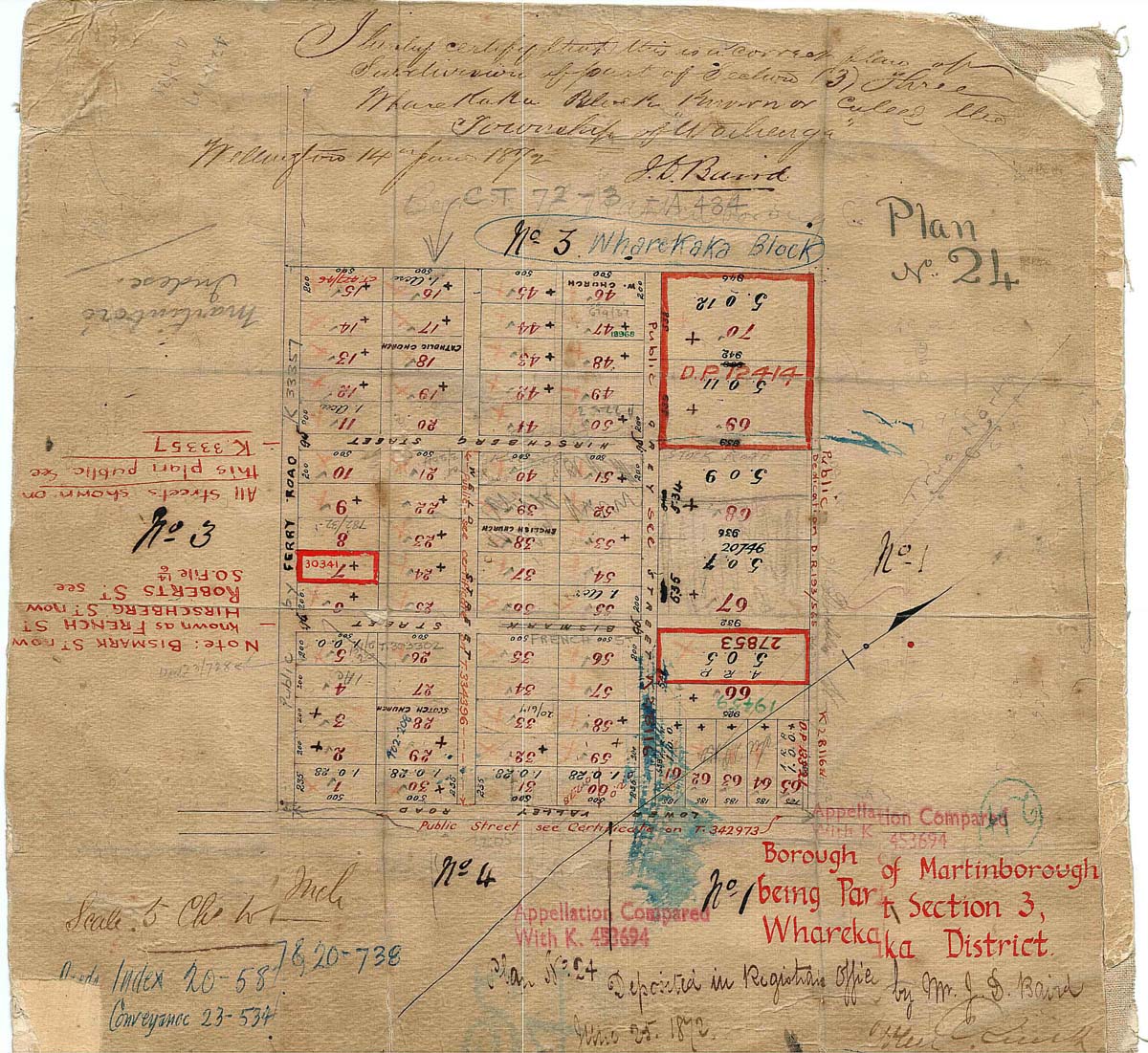

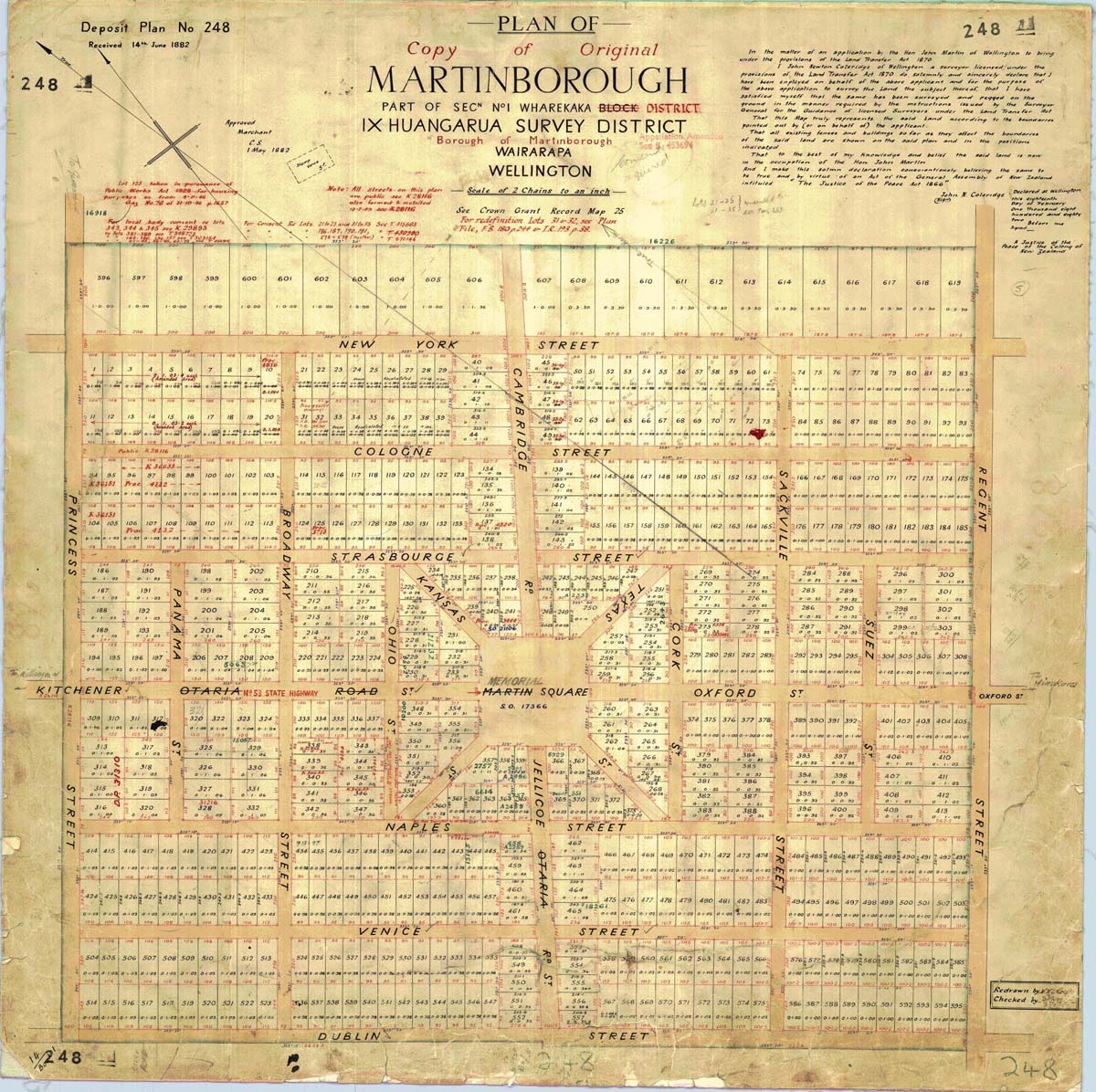

I am grateful to Mate Higginson, the Martinborough historian, for drawing my attention to a copy of a plan in his possession of a small township that was the earliest beginings of Martinborough town, dated 14 June 1872. After some difficulty with LINZ I managed to track down the original plan and requested a digital copy in colour of it. This is covered in many reference numbers and with help from LINZ staff additional documents and plans relating to the town can be located.

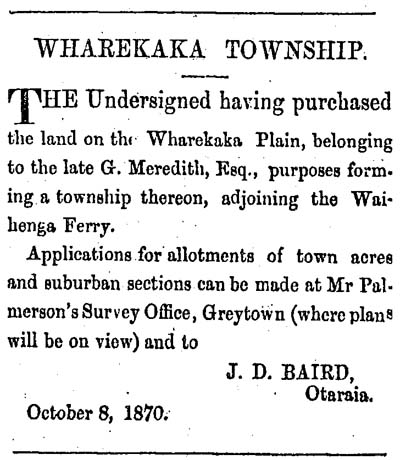

The first news of a town being planned in the vicinity of Martinborough was a series of advertisements in several newspapers which ran for some time. The example on the left was published in the Wairarapa Standard 26 October 1870 on Page 2. Clearly, the person selling the sections, James Daniel Baird, District Surveyor, had clear ideas of what he wanted the town to be named - Wharekaka - after the plain on which the land is situated.

The first news of a town being planned in the vicinity of Martinborough was a series of advertisements in several newspapers which ran for some time. The example on the left was published in the Wairarapa Standard 26 October 1870 on Page 2. Clearly, the person selling the sections, James Daniel Baird, District Surveyor, had clear ideas of what he wanted the town to be named - Wharekaka - after the plain on which the land is situated.

"The new Presbytarian Church which we were opening is built in the new Township of Bairdstown, on the Wharekaka Plain. This new township has been laid out, and the ground sold in allotments, by Mr Baird, one of the provincial surveyors. He also kindly granted the site for the church, and a ten-acre section has been secured for the future manse and glebe [ecclesiastic land]. It is a beautiful spot" (Wellington Independent 31 May 1872 on Page 2).

However, by the time the area was fully surveyed and lodged with the Registrar's Office, a third name appeared for the new town. Baird wrote:

"I certify that this is a correct plan of Subdivision of part of Section (3) Three Wharekaka Block Known or Called the Township of Waihenga. Wellington 14th June 1872. J. D. Baird"

The section layout of the town is above. Much of the writing on the plan is upside down, so

Clickhere for a rotated version.

The section layout of the town is above. Much of the writing on the plan is upside down, so

Clickhere for a rotated version.

K33357 = Record type 'Instrument (Document)' - refer to the plan that it is noted on when ordering so we can verify the number is correct.

It will be interesting to request some of these deeds and plans in due course to learn more about the early history of Waihenga Town. One interesting thing about the plan is Baird's provision for no less than four churches. Section 28 was set aside for the Scotch Church, Section 38 for the English Church, Section 18 for the Catholic Church, and Section 46 for the Wesleyan Church. They are suitably set apart from each other. The measurements on the plan are in links, so the small sections are 200 x 500 links = 1 acre. Section 70 is where the original Waihenga Cemetery is located, and in spite of the annotations on the map, the Presbyterian Church is on Section 30, not 28.

SO File 14/6 = Could be a plan file - order type 'Other Record' - refer to the plan that it is noted on when ordering. May not be available.

18968 = This is a DP Plan

27853 = This is a DP Plan

30341 = This is a DP Plan

19459 = This is a DP Plan

DP 12414 (is this a Deed Plan or a Deposited Plan?) = This is a DP (Deposited Plan)

Deeds Index 20-58 &20-738 = Deeds Index Records held at Archives NZ. May be searched on their 'Archway' website as indexes are digitised

Conveyance 23-534 = Deed Record held at Archives NZ, probably reference to Deeds Book 23 folio 534, but best to check with them. Deeds Books are not digitised

CT 72-3 = Certificate of title WN72/3

A484 = A Plan 484

On the 30th of May 1879 an article appeared in the Wairarapa Daily Times entitled Waihenga (From our own correspondent, May 27, 1879), with a review of current news from Waihenga. It is initially concerned about the parlous state of the money market and the "cruel screw of the New Zealand Banks". It then goes on to complain about Maori dogs worrying sheep:

"Mr McDougall, of the Lower Valley, proved very unfortunate with his sheep on Sabbath last. He found that no less than sixty in his flock had been worried, and it is supposed that several others not yet found have been bitten, and thus disabled. It arose from four savage and starved dogs belonging to the Maori pah between Mr McDougall's and Mr Russell's estates. All the dogs were given up by the natives, and were at once shot. The Maoris have promised to pay the loss sustained by Mr McDougall. It is high time to ask if the natives should be allowed to keep such numbers of savage brutes of dogs as they usually do".

The article continues, describing a plan for an extension to the existing Township of Waihenga (also known as Wharekaka and Bairdsville).

"The plan of the extended township is now published, and lies for inspection at the Post-office. It contains 200 acres of land cut up into sections of a quarter-acre each. It is expected that when the sale comes off all the sections will be taken up. The disposal of Mr Martin's land is looked forward to with good expectation. Already several buildings are planned, and the contracts are out. The plan is published under the name of Martinburgh [sic]".

The first advertisment to appear, offering sections for sale, was in the Wairarapa Standard (June 1879, Page 4), followed by many others published in several newspapers. Finally, a public auction of sections was held, and reported in the Evening Post on 24 November 1879 as follows (Volume XVIII, Issue 125, Page 2):

"SALE OF MARTINBOROUGH

A few days later, the Featherston Highways Board noted that Mr Martin was being a little high-handed in his plans for the new town, and "The Clerk was instructed ... to inform Mr Martin that, as he appears to have cut up and sold portions of a public road as Martinborough town sections, the sale thereof is illegal, and that the Board does not intend to relinquish its claim to the road (Wairarapa Daily Times, 2 December 1879, Page 2)". The plan used for selling sections in 1879 is shown below. Unfortunately, the original plan is currently not able to be found, but was in the hands of the Martin Family, Waitawa, when McIntyre copied it for publication at low resolution (McIntyre, 2002: plates following page 96).

The sale of the Martinborough Estate, consisting of 40,000 acres of agricultural and pastoral land in the lower valley of the Wairarapa, the property of the Hon. J. Martin, opened at the Athenaeum to-day. There was a good attendance. Mr. J. H. Wallace, the auctioneer, in the course of a few introductory remarks, observed that no doubt this sale would lead to the breaking-up of large estates all over the colony. Everybody was crying after land, and Mr. Martin had set the example by offering one of the finest districts in the colony.

Please note the area where the Ruamahanga and Huangarua Rivers meet on this map, which is quite different today. This was discussed earlier, and in connection with the land known as Pukepuke-o-Natea.

The surveyor pegging out the town was John Newton Coleridge, working on behalf of the Hon. John Martin of Wellington, and his declaration of authenticity was signed and witnessed 18 February, 1882.

It is of some historical interest why the town was laid out in such a way that the streets and sections are not aligned to North-South, but at an offset angle of 37.5°. It would have been so much simpler for future houses to be aligned facing north to get the maximum sun if the town had not been offset in this manner. Later plans reveal that the Township of Martinborough exactly abuts the earlier Township of Waihinga or Bairdsville as it was known, so simple logic dictates that this offset was set in place when the first township was laid out, and that the add-on Martinborough simply followed suit. Why then was the first township offset in this way? The image below solves this historical quirk once and for all. On the right is part of the 1941 Cadastral map showing the part of Martinborough which was once Bairdsville. On the left is part of map SO-10651 (1864) showing the Block known as Wharekaka No 3, with the location of Bairdsville marked in place. As you can see, the alignment simply follows the boundary of Block 3. Mystery solved !

The Immediate Aftermath: Post 1880

The Great Earthquake 1855 and the sale of Lake Wairarapa 1876 and again

The foundation of Hikawera at Kehemere

When preparing this web page it was not my intention to explore the developing story of Maori and European interaction in the Martinborough-South Wairarapa area folllowing the establisment of Martinborough township in 1879 and the formal acceptance of the section boundaries in 1882 as described above. However, there are some issues remaining, whose origins are well before 1880 and continued well after Martinborough was laid out for settlement. Amongst these issues, two are chosen for expansion:

Footnote 1:

Two other potential sources of fat and carbohydrate that were available in inland areas are Eels and Fernroot. The quantitative contribution of these foods to the diet of pre-European Maori is disputed, and not able to be addressed here. For further information on this issue, email Foss.Leach@gmail.com

(Return to text)

Footnote 2:

On 22 October 1773 when James Cook was off Black Head, just north of Porangahau, some canoes came alongside and asked for nails. Cook was intent on providing them with "Hogs, Fowls, Seeds, roots &c" (Cook 1961: 278), and when one of the chiefs came on board, Cook "brought before him the Piggs, Fowls, Seeds and roots I intended for him" (ibid.: 279). Mindful of the poor fate of similar gifts he had made in Ship Cove in Queen Charlotte Sound, Cook tried to impress on this chief that "proper care is takn of them there were enough to stock the whole island in due time, there being two Boars, two Sows, two Cocks, and four Hens; the seeds and roots were such as are most usefull (viz) Wheat, French and Kidney Beens, Pease, Cabages, Turnips, Onions, Carrots, Parsnips, Yams, &c &c" (279).

(Return to text)

Footnote 3:

On February 4, 1827, when D'Urville was off Tolaga Bay, "At 8 p.m. two canoes, which we had observed for some time paddling towards us, came alongside without any fear, and as though accustomed to see Europeans. They sold us some pigs, potatoes, and other objects of curiosity in exchange for hatchets, knives and other trifles...It may therefore be judged with what pleasure these articles were received, above all when they told us that pigs were plentiful at Tolaga, and that they would sell them at the lowest price... Te Rengui-Wai-Hetouma, chief of the New-Zealanders who came to visit us, announced himself as one of the principal rangatiras of the district, and wished to send his canoes ashore to procure pigs and potatoes" (Smith, 1908: 132). Next day, more Maori visitors came to the Astrolabe and "we obtained potatoes in profusion" (ibid.: 133).

(Return to text)